In the 19th century, Beijing refused becoming a dumping ground for a commodity from British India whose domestic consumption was outlawed, but export to China incentivized. This led to the Opium Wars between British Empire and the Qing Dynasty. Since then, narcotics have played a key role in abetting conflicts.

It has engendered civic and political dysfunction, leading to massive corruption, criminality, and facilitating a shadow economy rigged in the favor of a few shady operators.

War-ravaged Afghanistan produces more than 80% of the world’s opium and heroin, synthetic opiate byproduct made in ramshackle labs. Most of these find a way to the western markets, either via Iran and Turkey, or through the partially porous border with Pakistan.

Narcotics, combined with the failure of institution building, fragmented political authority, gaping trust deficit, warlord decentralization, myopia of international aid groups, and lack of a consensus, has led to the tragedy of Afghanistan — it ranks among the world’s poorest and most underdeveloped countries.

Conflicts & Drugs

Whether insurgencies and prolonged chaos and instability fuel narcotics, or the obverse, has been a chicken-and-egg question. Though conventional wisdom as well as scrupulous on-ground reportage and analysis suggests that narcotics is the axis around which the political economy of many of these countries revolve.

As Gretchen Peters mentions in ‘Seeds of Terror: How Heroin is Bankrolling the Taliban and Al Qaida’, a revealing book on the role of drugs in terrorism and conflicts, Afghanistan’s share of earnings from opium and heroin has been way more than Colombia.

A lot of what the Taliban did was analogous to the glitzy transnational cartels of Medellin and Cali who made it to the Forbes list. It also bore resemblance to the ultra-leftist insurgent groups such as FARC and ELA whose role varied from supply managers to kingpins in areas under their control

In 2009, she brought to global attention the un-ironical ‘Farcification of Taliban’. Now with the Taliban at helm of the regime in Kabul, the current situation is hard to predict.

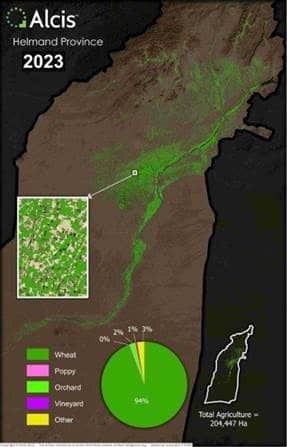

Helmand Imagery

With the help of precise geospatial analytics and actionable data, we can get near-real-time picture of the fields, as well as monitor supply lines. While tracking has got easier, the overall dynamics of this murky game remain unchanged.

Recent satellite imagery by Alcis, which provides geospatial information services for better understanding of conflict environments, shows 90% dip in opium cultivation in Helmand( one of the key regions of cultivation). After a Taliban imposed ban last year, it is an interesting development to watch out.

“Through the pioneering use of satellite imagery and machine learning, we are identifying the different winter crops that were grown this year and in recent years. The results allow us to generate maps of winter crop cultivation at a level of precision and accuracy that has never been done before across Afghanistan”, says Richard Brittan, Managing Director, Alcis.

New Game plan?

While on the surface it may seem that Taliban is leading its own ‘War on Drugs’, the reality is more complex.

Taliban has a complex and longstanding relationship with opium, exploiting it as a leverage, and dipping into it as a vital cash source to regroup and fund itself during the long insurgency and internecine warfare post 2001.

In the mid-90s, after occupying the vacuum left by rapacious warlords, it began formalizing tariff collection at the highways and border roads, protecting traffickers from roving bandit gangs.

At the same time, it gave some sort of relief to the destitute sharecroppers, trapped in a vicious debt cycle, and fearful of crops being destroyed by government or military. In the process, it sought to cultivate a reputation as ‘village robin hoods’, while entrenching itself as a key conduit in the narco traffic.

The last pages of ‘Return of the King’ by William Dalrymple, which focusses on the Anglo-Afghan wars, and can be read as an elegy to the ‘graveyard of empires’, depict farmers riled up by US-NATO drone attacks destroying their opium fields, and vowing to inflict a repeat of Soviet retreat on the western alliance.

From grassroots to the top echelons, all the stakeholders in the drug economy had a mutually beneficial, if not perfectly cordial, relationship with the Taliban.

Demand & Supply

Opium is a sturdy, drought-resistant crop that can be stockpiled without any risk of rotting. In this case, what matters more than the area under cultivation, is the tons stashed in secret warehouses.

Gretchen Peters, the journalist and long-time Afghanistan observer cited above calls the previous opium ban by the Taliban in 2000, amid mounting international protests and sanctions, akin to an ‘insider scam’. It is said that in the impoverished and cash-strapped hinterlands of Afghanistan, opium was, till recently, a mode of barter that could fetch anything from a TV, motorcycle, to a Kalashnikov.

Following the 2000 ban, the demand rose and the prices shot. Just like any other astute market speculator, Taliban dipped into its stockpiles, engaging in ‘buying low, and selling high’ tactics, earning a massive windfall. The roots of opium in Afghanistan are so deep that a former Afghan president’s brother was said to be deeply implicated in narcotics trade few years back.

Does the Taliban have something similar in mind this time as well, or with all trappings of state power under control, it genuinely wants to wean off the narco-led monoculture to make others fall in line ( warlords whose fealty to Kabul is absolutely transactional)? All of it remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, analysts from Alcis say that there won’t be any short-term opium/heroin supply reduction. However, if the decrease in cultivation continues next year as well, there could be a long term impact.

Disclaimer: Views Expressed are Author's Own. Geospatial World May or May Not Endorse it