A recent study analyzed open-source geospatial gridded layers at high spatial resolution, to estimate and predict the risk of snakebite for both humans and livestock, in the southern plains (the Terai region) of Nepal, where 57.3% of the country’s population resides. The study stated that lack of awareness and education about snakebites, and limited access to medical facilities, were hampering timely treatment.

The study was carried out by a group of researchers from institutes based out of Geneva, non-profits like MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières or Doctors Without Borders) and the Nepal-based B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences. It covered almost 13, 000 households and was published in the British journal Nature in December 2021. The study was the first of its kind in the Indian subcontinent. Surveys conducted for previous studies were localized to relatively small areas and focused on incidents of snakebite in just humans through epidemiological studies.

Globally, snakebite envenoming is regarded as a potentially life-threatening disease, killing over a one lakh people and causing disability in over four lakh more every year (see Box 1). Snakebite incidence in the Terai region for humans and animals, respectively, was estimated at 262 and up to 202 cases (depending on the species) per one lakh. According to data released jointly by the Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal, and the World Health Organization (WHO), about 20,000 people are admitted for snakebites to hospitals every year, of which, approximately 1,000 die. However, other sources claim that as many as 2,700 people die of snakebites every year in Nepal.

Snakebite incidents are clustered around poverty-ridden areas. Other factors like quality of houses, jobs, family members, etc., matter too (see Box 2). In the Terai region, the risk of snakebites in a household increased over 63 times if the Poverty Probability Index (PPI) — a poverty measurement tool — increased by a single unit.

Food storage was found to be the second-most important variable, increasing the risk of snakebite by 2.78 times, straw storage increased it by 1.78 times, and the addition of each kilometer in fetching drinking water increased the risk by 1.38 times.

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), showed that snakes are often spotted in areas of dense coverage. They also hide in places where food or straw are stored. NDVI appeared to increase the risk of snakebite by only 0.24 times (low degree of correlation) whereas sleeping on the floor increase the risk by 0.46 times (moderate degree of correlation). However, separate research in India showed an increased incidence of snakebites in rural Maharashtra, correlating with people’s habit of sleeping on the floor.

Places where food and straw are stored near houses are conducive for prey (rodents), resulting in frequent encounters between humans, domestic animals and snakes.

Nepal is predominantly an agrarian society where domestic animals play an important role. Loss of livestock results in economic burden on farmers. Major risk factors, as per the study, are animal sheds, straw storeroom, human modification of terrestrial system (HMTS), minimum temperature and animal density (pig and sheep). HMTS is associated with human pressure on terrestrial land based on an existing threat classification system that includes population density, cropland, pastureland, roads, railroads, navigable rivers and night-time light.

The strongest risk factor for increase in snakebites in domestic animals is the minimum temperature of the coldest month. It increases the risk of snakebite by 23.41 times. Density of sheep is the next-strongest risk factor, resulting in an increase of snakebite risk over eight times. Animal sheds increase risk over six times, while pig density increases it over2.27 times and straw storage 1.64 times.

The Poverty Probability Index (PPI) is based on a set of 10 questions prepared by experts in collaboration with international organizations. These questions probe the quality of housing walls, rooftops, number of bedrooms, availability of kitchen and toilets, phones, number of family members, types of jobs, and types of land. These indicators carry some specific marks to measure poverty. The latest version of the PPI for Nepal was created in October 2013 by Mark Schreiner of Microfinance Risk Management. While L.L.C. Indicators in the PPI for Nepal are based on data from the 2010 Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS), the development of the 2010 Nepal PPI was sponsored by Good Return.

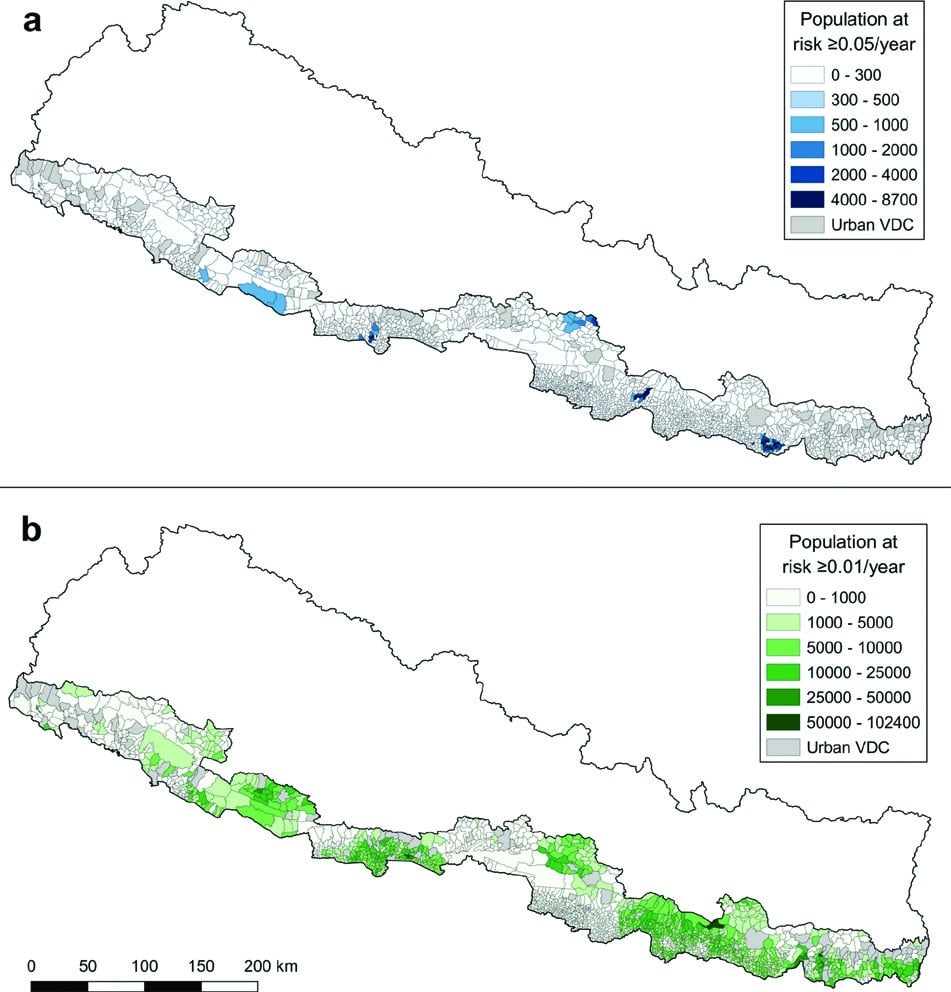

The research paper identified some of the areas at risk of snakebites in the eastern and central region. Residents of Saptari, Makwanpur and Sarlahi are at risk. A large number of people in many more districts fall in the high-risk zone if the risk threshold gets reduced. Places where the risk threshold is higher than 70% are Rupandehi (91.41%) Saptari (86.16%), Mahottari (86.11), Dhanusa (80.45), Makwanpur (73.89), Siraha (72.17) and Dang (70.79%).

This path breaking study was able to gather comprehensive data that can now be replicated in other countries and for other diseases. A great factor in the enablement of it is the recent proliferation and adoption of geospatial approaches that allowed direct and indirect estimation of the present and future risk of snakebite and other spatially distributed health and social problems.

© Geospatial Media and Communications. All Rights Reserved.